Sharks: Is there anything cooler in the ocean? From the tiny Dwarf Lantern Shark that is about the length of a pencil to the gigantic Whale Shark the size of a bus, sharks represent a fascinating and unbelievably diverse group of marine animals. It is no surprise that some aquarists want to take their appreciation of sharks to the next level by showcasing them in a home saltwater aquarium—but that requires plenty of planning, knowledge and a strong commitment to animal care.

Even smaller sharks require a serious amount of space, and all need pristine water conditions, so it’s important to realize that keeping a shark is a major responsibility. Sharks are not a suitable animal for the average hobbyist; only advanced aquarists need apply.

That said, let’s take a look at five types of sharks conducive to aquarium life and what they need to thrive.

Five Popular Saltwater Sharks for Aquariums

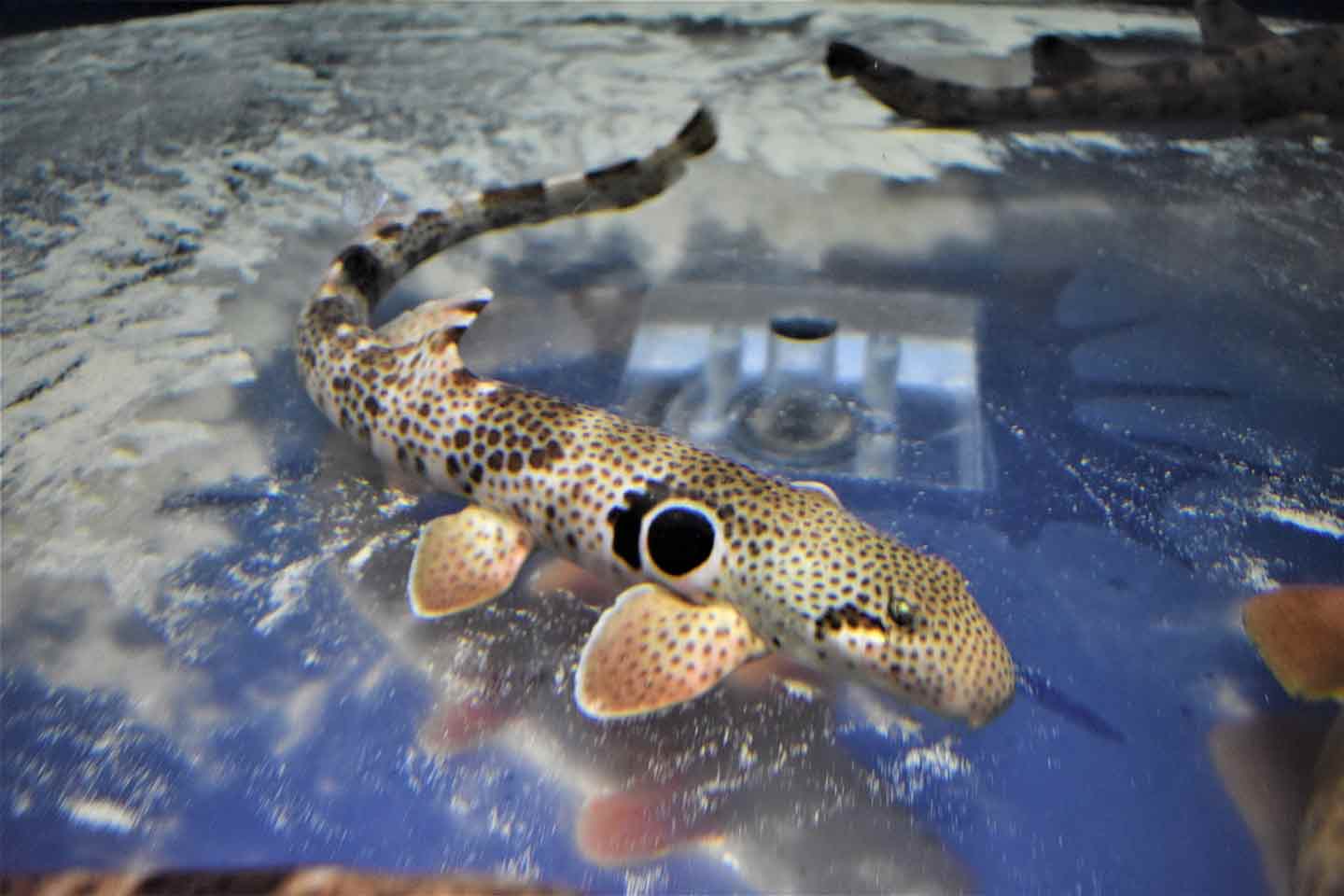

1Epaulette Shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum)

Maximum Size: 30”

Minimum Tank Size: 200 gal

Best Tank Mates: Aquarium fish such as tangs, damsels, anthias and other docile, mid-water saltwater fish (nothing aggressive or nippy like triggers, puffers, large angels, etc.)

These beautiful sharks are covered in small spots plus a characteristic pair of large spots called ocelli above their pectoral fins. This conspicuous marking resembles the shoulder decoration used on military uniforms to signify rank and is the origin of their common name.

Instead of swimming in the water column as we usually expect sharks to do, Epaulette Sharks use their muscular paired fins to climb over the sea floor. They are also called Walking Sharks because they use those strong fins to “walk” between coral heads at low tide.

In the wild, they feed mainly on crabs and worms, but in captivity they will accept most meaty marine food items that are small enough to fit in their mouth. Water temperatures should be stable between 75-82°F.

2Whitespotted Bamboo Shark (Chiloscyllium plagiosum)

Maximum Size: 36”

Minimum Tank Size: 300 gal

Best Tank Mates: Aquarium fish such as tangs, damsels, anthias and other docile, mid-water saltwater fish (nothing aggressive or nippy like triggers, puffers, large angels, etc.)

The color pattern of these sharks features numerous white spots that accent dark bands and saddles on a light-brown background. As bottom dwellers and substrate foragers, these sharks need the largest tank footprint you can manage.

They like to hide in rock crevices during the day and are the most active at night, which is when they prefer to eat, and will often search through the sandy substrate looking for food. Any large rocks or other structures should be placed directly on the bottom of the tank so they are as stable as possible; otherwise, your Whitespotted Bamboo Shark may topple them. Water temperatures between 72-78°F are ideal. In the wild, they mostly eat crustaceans and bony fishes, and in captivity they like to feed on squids, shrimps, clams, scallops and marine fishes.

3Coral/Marbled Catshark (Atelomycterus marmoratus)

Maximum Size: 28”

Minimum Tank Size: 200 gal

Best Tank Mates: Aquarium fish such as tangs, damsels, anthias and other docile, mid-water saltwater fish (nothing aggressive or nippy like triggers, puffers, large angels, etc.)

These beautiful little sharks are covered in black and white spots that often merge to form horizontal bars. An ideal aquarium for this species would be 300 gallons or more with a sandy bottom and a mix of open areas for swimming and rock formations to provide caves and crevices for the shark to explore and seek shelter in.

Coral Catsharks live in shallow, Indo-Pacific coral reefs, so they need warm, stable water temperatures ranging from 78 to 82°F. As active foragers, they prefer a diet of fresh or frozen silversides, shrimps, clams and mussels. These sharks have a small mouth and need appropriately sized food items.

4Speckled Carpet Shark (Hemiscyllium trispeculare)

Maximum Size: 30”

Minimum Tank Size: 300 gal

Best Tank Mates: Aquarium fish such as tangs, damsels, anthias and other docile, mid-water saltwater fish (nothing aggressive or nippy like triggers, puffers, large angels, etc.)

5Short-tail Nurse Shark (Pseudoginglymostoma brevicaudatum)

Maximum Size: 30”

Minimum Tank Size: 300 gal

Best Tank Mates: Aquarium fish such as tangs, damsels, anthias and other docile, mid-water saltwater fish (nothing aggressive or nippy like triggers, puffers, large angels, etc.)

How to Care For Saltwater Sharks

Space and stability are two of the main factors that will ensure your success in keeping aquarium sharks. The large aquarium size requirement is not just about having enough physical space for your shark to comfortably move around, but also about the volume being big enough to ensure your water quality parameters remain stable. System stability increases with water volume, so the bigger the better in this case.

Sharks can be messy eaters, and since they will likely consume any fish who currently serve as your “cleanup crew” and would normally take care of leftovers, it’s best to overestimate the amount of filtration your fish tank will need. A soft, sandy substrate is a must, as these sharks spend most of their time on the bottom, and rough or sharp rocks could scratch their belly. Since the sharks mentioned here are all nocturnal, or at least crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk), lower lighting is advisable if you’d like to see more activity.

In terms of diet, wild sharks eat whole food items, so it’s advisable to replicate this if possible. That’s not to say you shouldn’t cut larger food items into smaller pieces that are appropriate for their mouth size, but those food pieces should ideally come from whole animals so your sharks get the nutritional benefit of the most natural diet you can provide. Fish filets and peeled cocktail shrimp aren’t available in the ocean, so it’s best to try to replicate the nutrition your shark would get on a reef.

Remember: Sharks need a stable system with perfect water quality, excellent filtration and a diet of meaty foods, so they can only be recommended to experienced aquarists. If you are a novice aquarist, this is not the pet for you. It is unethical to keep these animals if you do not have enough marine aquarium experience and space to adequately care for them. Additionally, make sure you only purchase captive-bred sharks. Sharks who are acclimated to aquarium life and have grown up being fed a diet of previously frozen foods as opposed to hunting for live prey in the wild will fare much better as aquarium sharks in the long run.

Freshwater Sharks for Aquariums

The saltwater sharks discussed here cannot live in freshwater, but “sharks” for freshwater aquariums do exist. While not true sharks, these freshwater fishes, many of which are cyprinids (aka belonging to the minnow or carp family), do bear a strong resemblance to their ocean-going counterparts. With their high dorsal fins, torpedo-shaped bodies and active swimming style, they certainly have a shark-y look. Many species get quite large and shouldn’t be housed in aquariums less than 100 gallons.

These are some of the freshwater “sharks” that are commonly available in the aquarium hobby:

- Bala shark (Balantiocheilos melanopterus)

- Redtail shark (Epalzeorhynchos bicolor)

- Rainbow shark (Epalzeorhynchos frenatum)

Saltwater Sharks for Aquariums FAQs

Q:How much does a saltwater shark cost?

A:Saltwater sharks typically start at a minimum of $100 each but can be quite a bit more expensive than that. Epaulette sharks, for example, frequently cost close to $1,000, and short-tailed nurse sharks can be two or three times more expensive than that.

Q:Where can I buy a saltwater shark?

A:Captive-bred sharks can be purchased from reputable online retailers such as LiveAquaria and Oceans, Reefs & Aquariums (ORA), or occasionally from local fish stores that specialize in uncommon species.

Q:What’s the smallest saltwater shark species?

A:The smallest shark species that can be kept in a home saltwater aquarium is the Coral Catshark (Atelomycterus marmoratus), which grows to a maximum of 28 inches in length. The smallest shark species in the world is the Dwarf Lantern Shark (Etmopterus perryi), which maxes out at under 8 inches.

Q:What’s the best saltwater shark species for beginners?

A:There are no suitable saltwater shark species for beginners. Sharks are challenging and demanding animals to maintain. If you are a novice aquarist interested in keeping a shark, it’s best to spend years getting hands-on experience with general saltwater aquarium care before even considering getting a shark.

If you are an aquarist and think keeping a saltwater shark is the right choice for you, take the time to do as much research as possible before buying one. Purchasing a shark should never be done on a whim, and the care and keeping of these incredible marine creatures is not to be taken lightly. Read, research and talk to other aquarists who keep sharks, and make sure you can afford to install and keep an aquarium of the necessary size, as this is no small expense. Under the right conditions, sharks can be truly incredible and rewarding aquarium inhabitants.

Need some tank decor inspo? Check out these cool fish tank themes.

Expert input provided by Dr. Jessie Sanders, DVM, CertAqV, owner and head veterinarian of Aquatic Veterinary Services in the California Bay area.

More Fish Tips

Share: