The 13 Best Fish for Your Pond

1Koi

- Scientific name: Cyprinus carpio

- Adult size: Up to 2 feet

- Life expectancy: 25-40 years

- Best pond mates: Goldfish, Shubunkin, Orfe

Ornamental koi fish are selectively bred from wild carp, and exhibit an array of vibrant colors and patterns. Given their need for space and color-enhancing diets, koi aren’t the most beginner-friendly species. They are, however, tolerant of cold water. Koi can be overwintered in a koi pond that is at least 5 feet deep so it doesn’t freeze solid.

2Goldfish

- Scientific name: Carassius auratus

- Adult size: 10-12 inches

- Life expectancy: 10-15 years

- Best pond mates: Koi, Shubunkin, Orfe

Dr. Jessie Sanders, DVM, DABVP, the owner of Aquatic Veterinary Services in Santa Cruz, California, specifically recommends long-body goldfish like comets and common goldfish for ponds. “Fancy goldfish are not built for distance-swimming in a pond,” she says. Because they are a cold-water species like koi, goldfish do not require heated ponds as long as the water temperature doesn’t dip below 50°F.

3Shubunkin

- Scientific name: Carassius auratus

- Adult size: 8-14 inches

- Life expectancy: 10-15 years

- Best pond mates: Koi, Goldfish, Orfe

Shubunkin are a single-tailed goldfish species known for their calico pattern and long fins. Like koi, Shubunkin come in a range of colors, but their most striking feature is the pearl-like sheen of their scales. These are hardy fish best kept in groups of at least five, in a pond at least 2 feet deep with a volume of at least 180 gallons of water.

4Mosquitofish

- Scientific name: Gambusia affinis

- Adult size: 1-3 inches

- Life expectancy: About 1 year

- Best pond mates: Other small pond fish

Similar in size to fathead minnows, mosquitofish are a beginner-friendly option for new ponds. They’re often used in a pond ecosystem as biocontrol to reduce mosquito populations, but they also make great feeder fish for predatory species. Mosquitofish are tolerant of subpar water quality and are best kept in large schools in a pond with plenty of room to reproduce. They can be a little nippy, so don’t keep mosquitofish with shy or slow-moving species like fancy goldfish.

5Three-Spined Stickleback

- Scientific name: Gasterosteus aculeatus

- Adult size: Up to 4 inches

- Life expectancy: 3 years

- Best pond mates: Fish species who thrive in cool water

Sticklebacks are incredibly hardy; they can live in fresh, brackish or salt water. A unique variety for ponds, three-spined sticklebacks have slender, laterally compressed bodies with three spines along the back. They’re peaceful, schooling fish so they won’t bother shy pond mates. Keep in mind, however, that they don’t thrive in pond water temperatures above 70°F. They’re best kept in shaded ponds.

6Golden Orfe

- Scientific name: Leuciscus idus

- Adult size: Up to 24 inches

- Life expectancy: Up to 20 years

- Best pond mates: Koi, Goldfish, Shubunkin

Also known as the ide, the orfe is a freshwater fish similar in size to koi. The orfe has a decidedly carplike appearance with a plump body and short fins. Though typically silver in color, the golden orfe makes a stunning addition to large ponds (at least 1,000 gallons in volume). With adequate aeration and supplemental fish food diet, orfe can live up to 20 years.

7Chinese High-Fin Banded Shark

- Scientific name: Myxocyprinus asiaticus

- Adult size: Up to 24 inches

- Life expectancy: Up to 25 years

- Best pond mates: Koi, Goldfish, Orfe

Relatively new in the pond hobby, Chinese high-fin banded sharks are bottom-dwellers who thrive in large ponds with cool water. They have silver bodies with black, vertical bands and high dorsal fins. This species does well with other large pond fish like koi and, similarly, does best in temperatures between 55-75°F. They can be overwintered in deep ponds.

8Golden Tench

- Scientific name: Tinca tinca

- Adult size: 16-28 inches

- Life expectancy: Up to 20 years

- Best pond mates: Orfe, Goldfish, Koi

Suitable for freshwater and brackish ponds, tench are also known as doctor fish. They’re typically found in still, muddy waters, so they may be a good fit for ponds where more delicate species fail to thrive. They range in color from pale gold to dark red, sometimes with red or black spots on the sides and fins.

9Bluegill

- Scientific name: Lepomis macrochirus

- Adult size: 4-12 inches

- Life expectancy: 5-10 years

- Best pond mates: Large pond fish

If you’re stocking your pond with fish to eat, bluegill are a popular pick. They favor large ponds with plenty of vegetation, including sunken logs and tree stumps they can hide among. Bluegill are often raised as feeding stock for larger pond fish like bass. Unlike bass, however, they’re fairly tolerant of varying conditions and can coexist with smaller fish.

10Smallmouth Bass

- Scientific name: Micropterus dolomieu

- Adult size: 18-20 inches

- Life expectancy: 6-14 years

- Best pond mates: Large pond fish

Recommended only for very large ponds with cool water, smallmouth bass offer an exciting challenge for anglers and hobbyists. These fish require deep, clean water and a steady supply of forage fish like bluegill to feed on. Smallmouth bass don’t get quite as big as largemouth bass but may be less tolerant of warm or murky water.

11Walleye

- Scientific name: Sander vitreus

- Adult size: 20-40 inches

- Life expectancy: 10 years

- Best pond mates: Large pond fish

These nocturnal fish are a good fit for very large ponds that offer a combination of deep and shallow areas. As a predatory species, walleye are helpful in controlling populations of smaller fish like minnows or mosquitofish. They’re also known as yellow pike due to their olive/gold coloration. The name walleye, however, is a reference to the pearlescent sheen of their eyes.

12Channel Catfish

- Scientific name: Ictalurus punctatus

- Adult size: Up to 22 inches

- Life expectancy: 5-15 years

- Best pond mates: Large pond fish

Catfish are popular among pond owners, because they’re hardy and tolerant of varying conditions. They can grow quite large, however, and are likely to feed on small fish. Channel catfish are nocturnal and may stick to the bottom of the pond during the day, coming up to feed at night. They may also dig through sediment, making your pond look murky.

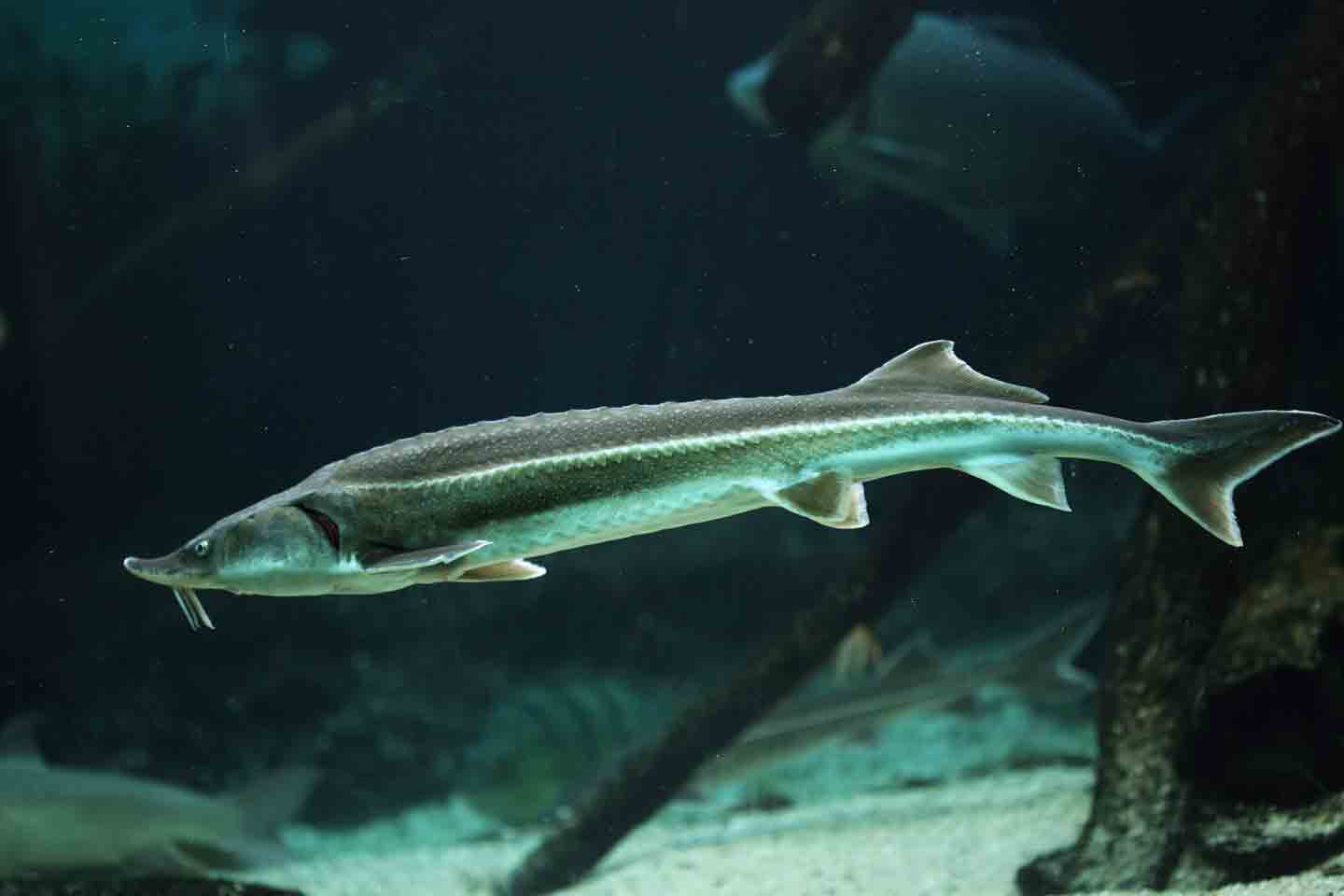

13Sturgeon (Sterlet)

- Scientific name: Acipenser ruthenus

- Adult size: 35-50 inches

- Life expectancy: 20-25 years

- Best pond mates: Large pond fish

Sturgeons require very large ponds of at least 1,000 gallons in volume. These fish are valued for producing high-quality caviar, but they can be challenging to keep due to their size. The sterlet is one of the smaller sturgeon species—but still averages 35 inches in length.

FAQs About Keeping a Pond With Fish

Q:How many fish can I have in my pond?

A:Dr. Serena Brenner, MS, DVM, CertAqV, consulting veterinarian and instructor at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine in Davis, California, suggests three factors for determining the number of fish to keep in a pond: waste load, swimming space and aggression level. She recommends starting with the fewest fish recommended for your pond’s volume and slowly adding more if pond conditions remain healthy and stable.

Q:What are the best eating freshwater fish choices?

A:If you’re stocking a pond with fish to eat, ornamental types of fish like goldfish and koi aren’t ideal. Some of the most flavorful freshwater fish include walleye, bluegill, perch, trout and catfish. However, many of the best fish for eating are most likely to thrive in large bodies of water like lakes and rivers—not small backyard ponds.

Q:What kind of fish can live with goldfish?

A:The best pond mates for goldfish are other active fish that thrive in similar conditions. Common goldfish can live with comets and shubunkins but may not be a good match for slower-moving fancy goldfish. Goldfish should not be kept with tropical fish.

A thriving backyard pond with fish isn’t a goal you can achieve quickly. Be thorough in researching the ideal species for your pond size and conditions, then take your time with setup. Don’t forget to research the costs involved in creating a backyard pond.

Expert input was provided by Dr. Jessie Sanders, DVM, DABVP, owner of Aquatic Veterinary Services in Santa Cruz, California; and Dr. Serena Brenner, MS, DVM, CertAqV, consulting veterinarian and instructor at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine in Davis, California.

Keep Your Fish Healthy

Share: