Parrots are often called hookbills, which is an avicultural term based on the shape of the beak or bill. This distinguishes parrots from softbills and other birds, such as doves and finches. The function of the parrot beak is for climbing, as well as manipulating and crushing objects.

Bird Beak Anatomy & Terminology

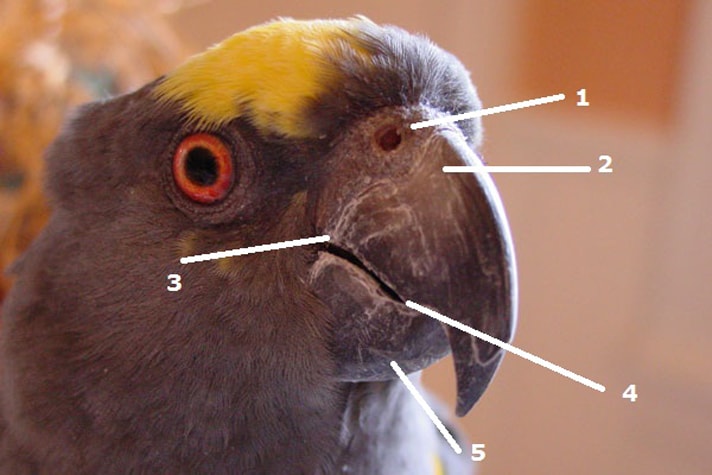

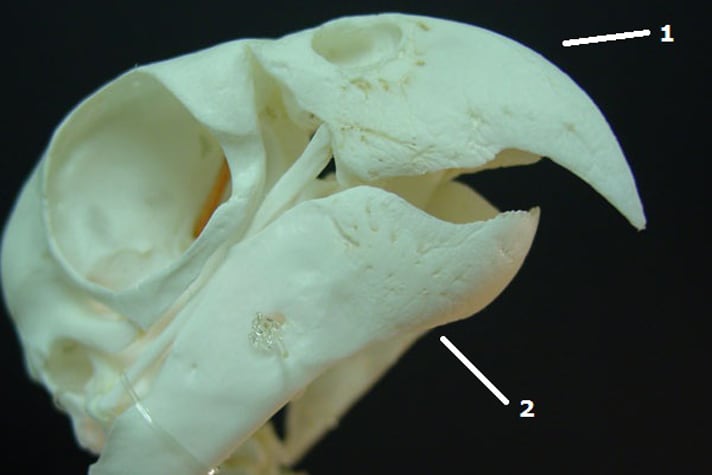

The rhamphotheca is the horny covering of the beak. Made up of a hard protein shell of keratin, it covers the bony jaws (the upper-maxilla and lower-mandible). The upper bill is called the rhinotheca, and the lower bill is called the gnathotheca. The cere is the soft, thick portion of the rhinotheca at the base of the upper beak where the nostrils are located. The beak keratin forms from the cere toward the tip at a rate of 1 to 3 mm/month. Continual wear by eating, chewing and rubbing on hard surfaces maintain the normal surface and length of the beak. The tomium is the cutting edge of the beak and the commisure is the corner of the mouth, between the upper and lower beak (Figure 1 & Figure 2).

Figure 1: Key anatomical features of the beak (rhamphotheca) are highlighted: (1) cere, (2) rhinotheca, (3) commisure, (4) tomium and (5) gnathotheca. Courtesy Laura Wade, DVM, ABVP (Avian)

Figure 2: The bony structures of the orange-winged Amazon parrot skull. Important beak structures are (1) Rostrum maxillare (upper jaw or maxilla) and (2) Rostrum mandibulare (lower jaw or mandible). Courtesy Laura Wade, DVM, ABVP (Avian)

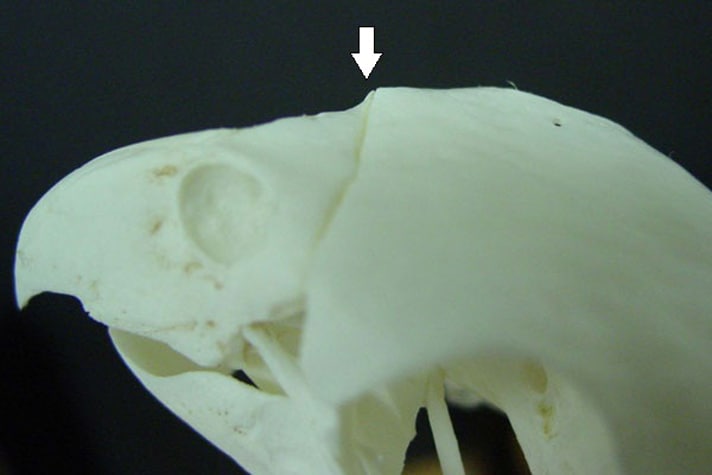

Parrots are unique in being able to move their upper beak independently and upward in relation to the lower beak. This is because of a unique joint, called the craniofacial hinge (Figure 3), which allows finer dexterity in manipulating objects and increased jaw pressure to crack large, hard nuts. In other birds, the upper beak is fused to the skull and does not move.

Figure 3: The craniofacial hinge (arrow), a joint between the rostrum maxillare and frontal portion of the skull. Courtesy Laura Wade, DVM, ABVP (Avian)

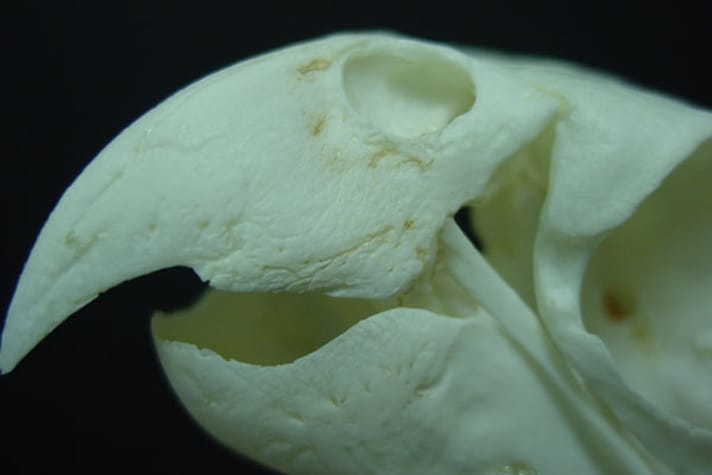

Under the keratin covering, the beak has an excellent blood supply and a network of nerve endings, which provide parrots an amazing tactile sensory ability. The most sensitive area is at the tip of the upper beak (Figure 4). The bones of the beak are not solid, but contain air spaces. The nasal and sinus cavities of the head also extend into the beak, and the maxilla contains a portion of the infraorbital sinus.

Figure 4: Close-up view of the grooves and pits in the bones of the beak where blood-vessels and nerves are located.Courtesy Laura Wade, DVM, ABVP (Avian)

Bird Beak Concerns

Bird Beak Developmental Problems

Congenital deformities from genetic or incubation abnormalities can show up soon after hatching. These may include variation in curvature and size of the beak. Developmental deformities may also occur during growth and are more common in hand-fed macaws and cockatoos. In macaws, a lateral deviation of the upper beak occurs, also known as scissors beak. In cockatoos, the curvature of the upper beak is increased, and affected birds appear to have an overly long mandible (mandibular prognathism). In severe cases, corrective orthodontic hardware may be used to correct the deformities.

Bird Beak Trauma

Trauma is quite common and most often the result of a bite wound from another bird. Male cockatoos are aggressive during the breeding season, and mate aggression is a common cause of crushed beaks and injury to the face and head. Larger birds can inflict more serious injuries to smaller birds; therefore, mixed flocks should be considered carefully. If a portion of the underlying bone is removed, the beak will still heal but will only grow over the shortened bone and often grows in unusual shapes (see additional information in Beak Care)

Bird Beak Nutritional Concerns

Malnutrition is a common cause of softening and flaking of the beak. Vitamin-A deficiency is likely the most common cause, especially in birds on a nutrient-deficient diet. In severe cases, the beak may also grow at an abnormal rate. This is because beta carotene, which is a precursor to vitamin A, is especially important in the formation of keratin and the normal turnover of epithelial structures, like the skin, feathers, nails and beak.

Ensuring pellets are part of the diet, as well as orange and green fruits and vegetables (e.g., carrots, sweet potatoes, squash, red peppers, dandelion, mustard and beet greens, kale, spinach, cantaloupe, papaya, etc.), can help a pet bird get the nutrition it needs to maintain good health. Vitamin-A toxicosis can also cause similar signs as vitamin-A deficiency, so be careful of over supplementation of powders and drops.

Metabolic Diseases

One of the more common causes of an overgrown beak is liver disease. Birds that are overweight are prone to the development of hepatic lipidosis (fatty liver), which often interferes with the metabolism of amino acids necessary for normal beak growth. The most important of these is glycine. Keratin is rich in glycine and, in normal situations, the liver can make glycine from other amino acids.3 When glycine is deficient, the liver also cannot detoxify or make bile acids.

Birds with overgrown beaks due to liver disease often appear in adequate health early on, yet their liver function is usually significantly reduced. Often, there are also be feather color/quality abnormalities concurrently. Early identification and medical intervention is essential in preventing end-stage liver failure. Birds with liver disease may need to be supplemented with additional glycine, which can be found in some meats seeds, legumes, and egg whites, in addition to other therapeutics.

Bird Beak Infections

The beak is a common target for a number of infectious disease processes psittacine beak and feather disease (PBFD) virus is caused by a circovirus and can affect a wide range of parrots. Beak lesions are common in cockatoos and include beak thickening, elongation, ulceration and fractures. Birds with PBFD often also lose their feathers on the head and body. Other viruses that affect the beak include poxviurses and polyomavirus. Bacterial and fungal infections may be associated with trauma or sinus infection. Mites such as Knemidokoptes cause inflammation and proliferation of the beak and are most common in budgerigars.

Cancer

Although rare, cancer of the beak is possible, especially in older birds. Squamous cell carcinoma is reported most often, but also melanoma and fibrosarcoma.

Bird Beak Care

In most situations, a healthy parrot beak does not need to be trimmed on a regular basis. The parrot rhinotheca normally has a long, sharp tip, which is more pronounced in macaws, and because of this, many inexperienced owners request veterinarians or groomers perform a beak trim. Birds that do not have access to or choose not to chew hard surfaces (e.g., wood, mineral blocks) often get a build-up of keratin, which can be carefully sanded by a veterinarian using a rotating tool. Beaks should never be trimmed at home.

A beak that starts to grow long or asymmetrically indicates that the bird should be seen for medical evaluation. The diet should be carefully reviewed for any possible deficiencies or excesses. Blood work may be obtained to assess the liver function. Treatment may include optimizing the pet bird’s diet, vitamin supplements and liver support. Periodic trimming may be required for a time to allow the bird to maintain normal grooming and eating ability. Often, there is a period of several months before changes in the body affect the beak.

The beak can be damaged especially when a bird flies into a hard object (window, ceiling fan or the floor), gets caught in bird cages or toys or is injured by another bird. Blunt trauma from landing — usually the result of an improper wing-feather trim — can cause a fracture of the tip of the beak, which is painful and can bleed profusely. Pet birds are sometimes temporarily unable to climb, groom or eat and may need pain medication and antibiotics. Sometimes, the resulting growth of the beak may be altered.

Injuries from other birds often involve the region of the beak near the cere and can include punctures, fractures or complete severing of the beak. These require immediate veterinary attention and often involve surgical repair and hospitalization. Owners should carefully supervise their flock and ensure that incompatible birds cannot access each other.

Ways to ensure a healthy beak include:

- Annual physical examination to ensure optimal health, weight and beak structure.

- A well-balanced diet, including vitamin-A containing fruits and vegetables.

- A proper wing-feather trim to allow for safe-landing and turning.

- Environmental safety prevention including flock interaction management.

- Appropriate chewing and beak rubbing outlets (wooden bird toys and perches, cuttlebone, mineral block, cement bird perches).

- Periodic blood sampling to assess internal health and liver function.

Posted by: Chewy Editorial

Featured Image: Pavel Boruta/Shutterstock.com

Share: