Camallanus worms are among the most commonly encountered internal parasites for aquarium fish and may infect a wide range of fish species, from guppies to goldfish. Read on to learn about how your aquarium fish can suffer from Camallanus worms how you can identify, treat and prevent these worms from infecting your fish.

Detecting Camallanus Worms in Aquarium Fish

Although many aquarists strongly associate the disease with guppies, mollies, loaches, dwarf cichlid fish, angelfish and discus, most types of aquarium fish can be affected.

Light infections of Camallanus worms are difficult to detect. Serious infections can be indicated by the presence of red, thread-like worms emerging from the anus of the aquarium fish. Mature Camallanus worms are a couple of millimeters long.

Other symptoms of Camallanus worms in aquarium fish include:

- Abdominal bloating

- Wasting

- Disinterest in food

Well-maintained fish may be infected without exhibiting any symptoms at all, and Camallanus worms are fairly commonly found among wild fish without any obvious link between infection and mortality. But negative environmental pressures such as overcrowding, poor diet and poor water quality will reduce the immune response of infected aquarium fish, making it easier for the worms to multiply and cause damage to their host fish.

Pathology of Camallanus Worms

There are numerous species of Camallanus worms, and while some parasitize only a limited range of fish species, others can be found in many different hosts.

The North American species Camallanus oxycephalus has been found in shiners, sunfish and bass, among others, and the South Asian species

Camallanus anabantis has been recorded from hosts as diverse as clariid catfish, spiny eels, barbs and gouramis.

The species most often implicated in infections of aquarium fish is the East Asian species Camallanus cotti. In the wild, this species infects a range of hosts including gobies, bagrid catfish and carp, but in aquaria and ponds it can be found parasitizing other types of fish as well, most notably livebearers, rainbowfish, loricariid catfish, cichlid fish and labyrinth fish.

A second species, Camallanus lacustris, from Europe and West Asia, is sometimes implicated as well. Again, this species naturally infects a range of hosts including eels, sticklebacks, and perches, and has been reported from an even wider range of hosts under a fish aquarium and pond conditions. Mature worms are red because they feed on blood. In addition, their activities irritate the digestive tract and adjacent organ systems, potentially causing internal bleeding and secondary bacterial infections.

Camallanus Worms Life Cycle

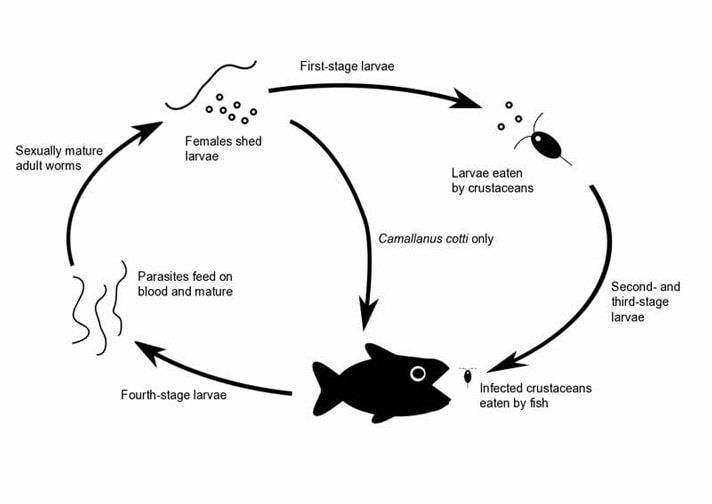

The life cycle of Camallanus worms passes through three key phases:

- A free-living stage

- A series of molts during which time the worms infect an intermediate host (a crustacean)

- Another molt then takes place in the final host (the fish).

After mating, mature females begin the cycle by producing large numbers of first-stage larvae. When the fish defecates these will be carried out into the environment. These larvae quickly settle out onto the substrate where they wiggle about in an enticing way, thereby tricking small crustaceans into eating them. Once that happens the larvae move into the host’s gut where they feed and grow.

By Neale Monks

Known intermediate hosts include Cyclops and Gammarus, but Daphnia have not (yet) been observed to carry the parasite.

Brine shrimp (Artemia) don’t normally carry the parasites because they’re reared in high salinity environments that Camallanus worms cannot tolerate. Within about a week they will have molted twice to form inactive third-stage larvae that sit inside the host. Should the crustacean be eaten by a fish, the third-stage larvae become active and start feeding again, eventually molting twice to form the sexually mature male or female adult worms. These are the distinctive red worms aquarists see protruding from the vents of infected aquarium fish.

The length of time it takes the life cycle to complete varies with temperature and for different Camallanus species, but in the case of Camallanus cotti it takes less than a month at 77 degrees Fahrenheit.

Most Camallanus species cannot complete their life cycle without an intermediate host, but Camallanus cotti is unusual in being able to skip this stage, and mature females produce first-stage larvae that can infect other fish directly if they do not find a suitable crustacean host first. Possible pathways include cannibalism and ingestion of feces produced by infected fish.

Camallanus Worms Treatment for Aquarium Fish

Antihelminthic medications are essential for treating Camallanus infections.

There are numerous medication options for treating Camallanus worms in aquarium fish including fenbendazole, levamisole, and praziquantel. These do not necessarily kill the worms, and in some cases only paralyze them, which results in them being pushed out of the gut and into the aquarium (which the aquarist will see when the pink or white worms emerge and detach from the anus).

Within 24 hours of medicating the substrate should be thoroughly cleaned to remove the worms. Normally three treatments are required, each one week apart.

Antihelminthic medications are usually toxic to snails and shrimp, so these animals should be removed before use. Antihelminthic medications may be toxic to fish if used other than as described by the manufacturer, and when treating expensive or delicate fish veterinarian advice is highly recommended. Because Camallanus cotti in particular can infect other fish directly, it is best to treat all livestock simultaneously rather than to move only the obviously infected fish to a hospital aquarium.

Preventing Camallanus Worms

Quarantining new livestock and treating prophylactically with an antihelminthic medication is recommended. Since Camallanus worms infect crustaceans, such fish food should generally be avoided, or at least sourced only from ponds known to contain no fish. While Daphnia don’t appear to carry these worms, if collected from ponds containing fish, any Cyclops captured with the Daphnia are quite likely to bring the parasite with them.

Posted by: Chewy Editorial

Featured Image: Via iStock/negaprion

Share: