If you’ve ever adopted a healthy, happy animal from a shelter, you probably have Dr. Lila Miller, DVM, to thank—and so does your pet.

She transformed the lives of countless pets, developing the first vet-written guidelines for shelter animal care, which are now used in facilities across the country. She’s educated a generation of students about issues shelters face. And she’s blazed a trail for women of color in veterinary medicine.

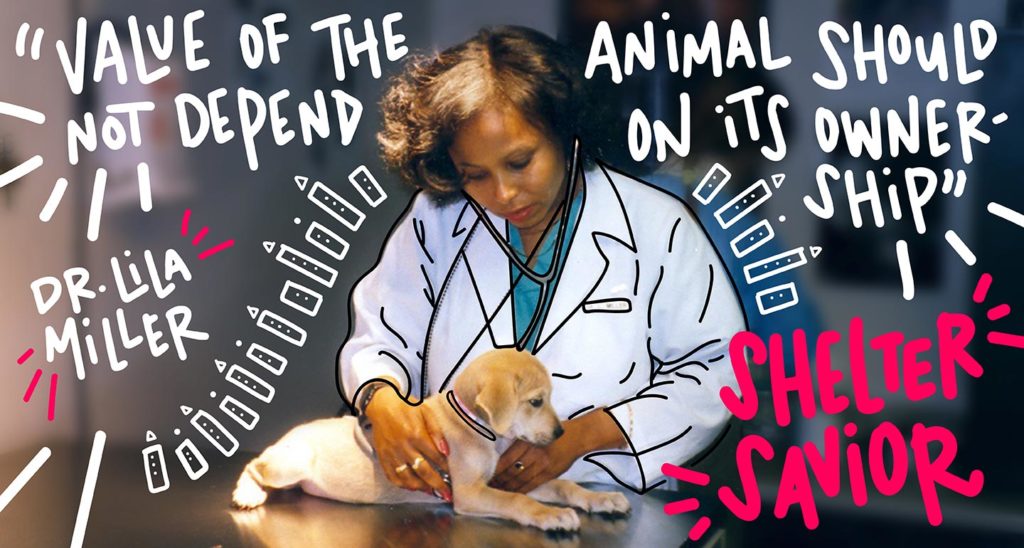

Through her 40-year career with the American Society for the Prevention of Animals (ASPCA), one simple belief has guided her work: “The inherent value of the animal should not depend on its ownership,” she says. “[All] animals have value.”

An Unstoppable Force

Born and raised in the New York City neighborhood of Harlem, Dr. Miller ignored the warnings of her high school adviser, who told her that becoming a veterinarian, a dream she held since she was 5, was an unrealistic goal for a young black woman in the 1970s.

“There were hardly any women or people of color who were veterinarians [at the time],” Dr. Miller recalls. But she wasn’t discouraged.

In 1973, the year she was admitted to the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine in Ithaca, New York, the program accepted about 65 students, she says. Just 14 of those students were women—and only two of those women, Dr. Miller included, were black.

At Cornell, Dr. Miller often felt unfairly singled out because of the color of her skin. Teachers graded her more harshly than the white students, she says. One professor called her and another student “black panthers” in the middle of a class. The first and only time she’s ever been called the n-word was on campus. But she was determined to persevere.

Dr. Miller was also required to attend classes in horse-dwelling barns, even after discovering she was severely allergic to horses. In her junior year, she was hospitalized after a near-fatal attack.

Unsure of whether she would be able to finish the program, Dr. Miller bravely went to the dean of her college with her concerns.

“He told me, ‘Lila, you’re a guinea pig in this program. If you don’t finish it, they’re not going to let any more black students in for the foreseeable future,’” she says. “Talk about pressure. I didn’t go there to make waves or blaze trails. I was just trying to fulfill a childhood dream.”

Dr. Miller responded to that challenge, vowing to complete the program more quickly.

She graduated in 1977, earning her degree a year early and becoming one of the first two trailblazing black women to graduate from Cornell’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

Revolutionizing America’s Shelters

Degree in hand, Dr. Miller returned to the city, where a mentor offered her a job at an ASPCA shelter in Brooklyn. She loved working with homeless animals, but was appalled by the neglectful practices that were common in shelter medicine at the time. Animals who appeared sick or injured often went untreated. Even healthy-seeming animals went without preventative care like vaccines.

Dr. Miller knew the animals in her care deserved better. So she took action, designing and implementing new guidelines to ensure the humane treatment of shelter pets.

“We [trained] staff how to handle animals appropriately, and we started vaccinating and deworming animals that appeared otherwise healthy,” she says. “That was a hugely immersive project.” Dr. Miller’s guidelines also replaced the practice of euthanization by decompression chamber with a more humane injection of euthanasia solution.

That experience set the course for the rest of her career. Dr. Miller served as director of ASPCA’s Brooklyn Clinic from 1982 to 1997, eventually rising to the position of vice president of shelter medicine for the national organization. She implemented sweeping changes: writing the ASPCA’s first Animal Care Supervisor’s Manual, which laid out health care and adoptions protocols for animal care staff; editing the industry’s fundamental texts in shelter medicine; teaching her colleagues to recognize signs of abuse in animals; and designing the first internet courses on shelter medicine and animal cruelty.

She also returned to Cornell in 1999, the place where it all began, to co-organize the first-ever shelter medicine course at a veterinary college. Though she retired from her full-time work at the ASPCA in 2018, she still guest lectures at Cornell. And in 2014, the school where she once felt like an outsider awarded her its highest alumnus honor, the Salmon Award, celebrating her pioneering work.

So much for not making waves.

Read more:

Share: