Chestnuts on Horses: What Are They, and Why Do Horses Have Them?

Photo by Somogyvari/iStock / Getty Images Plus

Let’s talk about chestnuts—but not the nut, or even the coat color. If you’ve ever run your hand along the inside of a horse’s leg or under their fetlock (aka ankle), and your fingers caught on a callused area or a patch of prickly horn sticking out, you’ve found their chestnut and ergot, respectively. Did you know that chestnuts and ergots are likely the remnants of extra toes horses used to have?

Read on to learn the fascinating reason why these two structures exist, the purpose they serve today, and how to take care of them.

What Are Chestnuts on Horses?

Chestnuts on horses are bundles of keratin—a fibrous protein that also makes up the horse’s hooves, mane, and tail, as well as your own hair and nails.

Most horses have four chestnuts and up to four ergots each. Some breeds of horse, like the Icelandic, along with zebras, donkeys, and mules, typically have chestnuts on just the front limbs.

Each individual animal’s chestnuts and ergots are unique, which means that these calluses are technically the equivalent of our human fingerprints!

“Chestnuts and ergots are remnant structures from evolutionary history, possibly former toes,” says Jeremy Frederick, DVM, DACVIM, owner of Advanced Equine of the Hudson Valley, an ambulatory veterinary practice based in Wappingers Falls, New York.

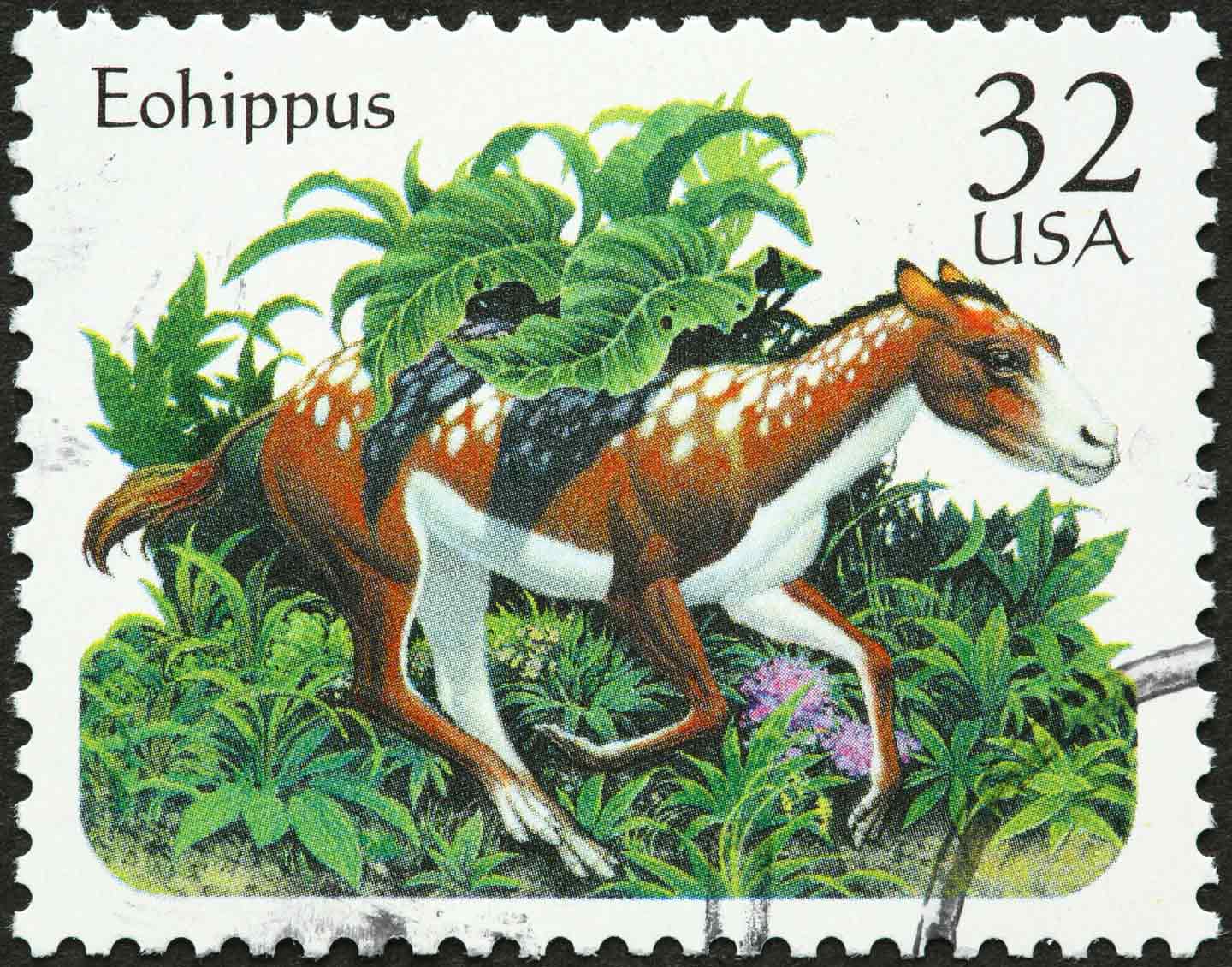

Back in prehistoric times (roughly 34–56 million years ago) the modern horse’s primitive ancestor, called Eohippus, had four toes in the front legs and three in the hind. Each toe ended in a small oval-shaped hoof.

raclro/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Over time, the middle toes—also known as the third metacarpal (on the foreleg) and third metatarsal (on the hind leg), or cannon bones—became more developed and longer, and the middle toes (phalanges) started bearing more of the weight. Experts believe this evolutionary trait developed to allow horses to run faster.

Over time, those middle toes evolved into horses’ present-day hooves. Chestnuts and ergots are believed to be vestigial toes, meaning the shrunken remains of some of the other toes.

What Is the Difference Between a Chestnut and an Ergot?

fuen30/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Chestnuts and ergots have some things in common, but they’re not exactly the same.

“Both the chestnut and the ergot are intimately connected to the underlying dermis (skin) and continue to grow very slowly throughout the horse’s life,” says Sharon May-Davis, MS, PhD, an equine lecturer, researcher, and scientist based in the Greater Newcastle area of Australia. “The basic composition of ergots and chestnuts are the same—keratin. Keratinized skin cells, to be specific.”

The differences between the two are mainly in their shape and location. The chestnut is the most variable in shape, being oval to bean-like in appearance in the foreleg (above the knee/carpus, on the inside of the leg) and smaller in the hind (below the hock, also on the inside of the leg).

On the other hand, the ergot, which is shaped like a comma, is positioned on the underside of the fetlock. “The size of both structures is generally proportional to the size of the horse,” says Dr. May-Davis, noting that there is significant variation between various breeds and individuals.

Hooves that stay wet for prolonged periods of time are prone to cracks, abscesses, and a bacterial infection called thrush. The ergot is thought to steer some of the water away from the horse’s lower legs—potentially helping to prevent these concerns as long as they are not standing in water or mud for extended periods

Recommended Products

Do Chestnuts and Ergots Hurt Horses?

Under normal conditions, no, neither chestnuts nor ergots cause the horse any pain. They are made of avascular, aneural calloused horn cells, which means they have neither blood vessels nor nerves. Horses can’t feel their chestnuts and ergots. Only if they are accidentally—or purposefully—ripped out from the skin will they bleed and cause the horse pain at the site where they attach to the sensitive skin.

How Do You Care for a Horse's Chestnuts and Ergots?

The short answer is: You don’t! In most cases, leaving your horse’s chestnuts and ergots alone is the best thing you can do for them. Many will shed their outer layer on their own and stay a shorter length.

This being said, if shedding does not occur properly, ergots can grow long enough to interfere with the proper placement of leg boots (protective gear worn on the horse’s legs), or chestnuts can catch on things and get ripped off.

To avoid this, you can carefully trim them, using either your fingernails or your farrier’s hoof knife. Break off excess horn while being careful not to cut too close to the base and to never cut the skin itself. In short, treat them like you would your own overgrown fingernails.

Fun Fact: Both chestnuts and ergots emit a strong “horsey” smell.

“In some cases, large chunks of horn will fall off chestnuts and ergots when the horse is being groomed,” says Dr. Frederick. “This is not a concern, but horse owners should avoid aggressively peeling them off when they are not loose, as that can cause discomfort.”

As an equestrian, you might come to conclude that chestnuts and ergots are two of the lowest-maintenance parts of your horse’s body. These callosities simply require monitoring, as they shed on their own for the most part.

Expert input provided by Jeremy Frederick, DVM, DACVIM, owner of Advanced Equine of the Hudson Valley, an ambulatory veterinary practice in Wappingers Falls, New York; and Sharon May-Davis, MS, PhD, an equine lecturer, researcher, and scientist based in the Greater Newcastle area of Australia.

This content was medically reviewed by Chewy vets.